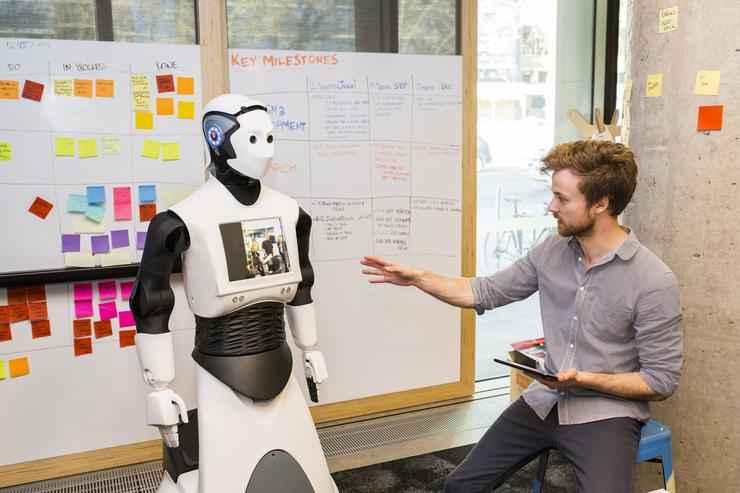

Chip with William Judge, robotics innovation manager at CBA

We know exactly what the robots of the future will be like. We’ve already seen them.

In TV series Humans the ‘synths’ are docile servants that look just like us save for their stiff movements and electric green eyes. The ones in I, Robot are less humanoid, with a white gloss shell and circa-2004 Apple aesthetics. Ava in Ex Machina is somewhere in between, with a skin-covered face and exposed electronic innards.

Whatever form they take, we can picture them caring for the elderly, carrying the shopping, driving trains, serving coffee, doing physiotherapy, running errands: our docile, domesticated servants.

In August last year, a partnership between Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), real estate giant Stockland, the Australian Technology Network of Universities and University of Technology Sydney started work towards achieving this vision.

In the months since, researchers have been busy preparing Chip – their 1.7 metre tall, 100kg, $300,000 android – to meet the public and start work in the real world.

Chip is fast mastering the nuances of human interaction, can move autonomously around its environment and is forming some kind of social intelligence.

But there’s a far more significant, non-technical challenge to overcome: our sky-high, sci-fi expectations.

Chip on the new block

CBA’s Innovation Lab in Harbour Street, Sydney took delivery of Chip – a model REEM from Spain’s PAL Robotics and the only one of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere – eight months ago.

The robot has two stereo cameras for eyes, lasers to map its surroundings, 16 ultrasound sensors to navigate obstacles, microphones and speakers to listen and talk and a touch screen on its chest.

Since its arrival, the ‘CANdroid’ – as it is known within CBA – has been the subject of continuous testing and tinkering at the hands of researchers from QUT, UTS, RMIT, Curtin University and University of South Australia and the bank’s own robotics team.

Their work means the robot is able to move around autonomously; detect, track and recognise faces; understand English and Mandarin; and perform physical interactions like giving people hugs, high fives and fist bumps. Those capabilities laid the foundations for the next stage of research: figuring out the boundaries and best practice in human-robot interactions.

“The social aspect of social robotics is so important, it is about understanding how people interact with technology, particularly technology that we might deem as artificially intelligent, and how we can create new technologies that better understand humans and interact with a social intelligence,” says William Judge, robotics innovation manager at CBA and Chip’s ‘dad’.

“Social robots are increasingly making their way into our daily lives,” Judge says, pointing to the likes of Amazon Alexa and Google Home. “People are beginning to interact heavily with these devices and in some cases form emotional bonds, similar to how many people may feel about their smartphones. We are therefore already starting to anthropomorphise or humanise technology, but technology doesn't often give us the same treatment in response.”

Rolling-out

In order to make Chip “just a bit more human” as Judge puts it, in December last year, Chip was rolled-out, quite literally, to Stockland’s Merrylands Shopping Centre in western Sydney, to meet the public.

"We’re interested in how robotics could be used in our business parks and logistics centres, shopping centres and our residential and retirement living communities," Stockland CEO Mark Steinert said at the time, "this partnership is about defining the future rather than waiting for it to happen to us."

Three experiments were carried out over the day: the first of which saw Chip guide shoppers to a particular store in the centre. In the second Chip was 'hired' by retailers to advertise their products, and during the third Chip attempted to persuade shoppers to try a chocolate sample.

“In the final experiment we observed some interesting behaviour when peopled interacted with the robot, namely that the social strategies that a human would typically employ to attract attention were not effective for the robot,” Judge says, “and there was a significant 'grouping' effect where people would prefer to approach the robot in larger numbers rather than individually.”

The findings go beyond interactions with the physical robot, Judge explains.

“Some of the work and research we have done so far is focused on understanding how people interact with machine learning algorithms in a robotic context, something that is useful to understand from a broader banking product perspective,” he said.

A current research project, working with University of Technology Sydney's Social Robotics Research Lab, is looking at privacy in machine learning systems, particularly in regards to face recognition algorithms.

“Face recognition systems obviously need to collect data about people's faces in order to function, but the question is how do you do this in a way that creates a positive user experience and maintains trust in the system, and can a robot help?” says Judge.

Great expectations

Chip is making great strides on its three wheels. It is being continuously updated and more public interaction experiments are being planned. Yet one of the biggest challenges facing Chip remains: the weight of expectation.

All new technology comes with baggage, former Intel anthropologist Genevieve Bell, now a professor at the Australian National University, explained at a digital summit in Canberra last month.

“All of this transformation happens against the landscape of the socio-technical: all of our imaginations. We’ve been told how this technology will work for decades before it arrived. We were told by Hollywood, if you were lucky you were told by the BBC, because that at least suggested it wasn’t going to work as well,” she said.

This leaves a significant expectation gap between how advanced the technology actually is and how advanced we believe it to be.

“Every piece of technology that comes along has a back story and that back story isn’t just a technical one. It’s one that’s been both utopically and dystopical portrayed in the books we read, in the television we saw, in the movies we saw,” Bell explained.

Since most people have been exposed to a wealth of fictional examples of what a social robot should be like – be it Star Wars’ C3P0, Marvin from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, even Rosie, the robot maid from The Jetsons – Chip now has a lot to live up to.

“We tend to find that there is a significant expectation gap between where people think the technology is at, largely due to science fiction and novelty effects, and what the technology is currently capable of doing,” explains Judge.

“It can be surprisingly difficult to surprise and delight when people think that general 'human-like' AI is just around the corner,” he adds.

Join the CIO Australia group on LinkedIn. The group is open to CIOs, IT Directors, COOs, CTOs and senior IT managers.